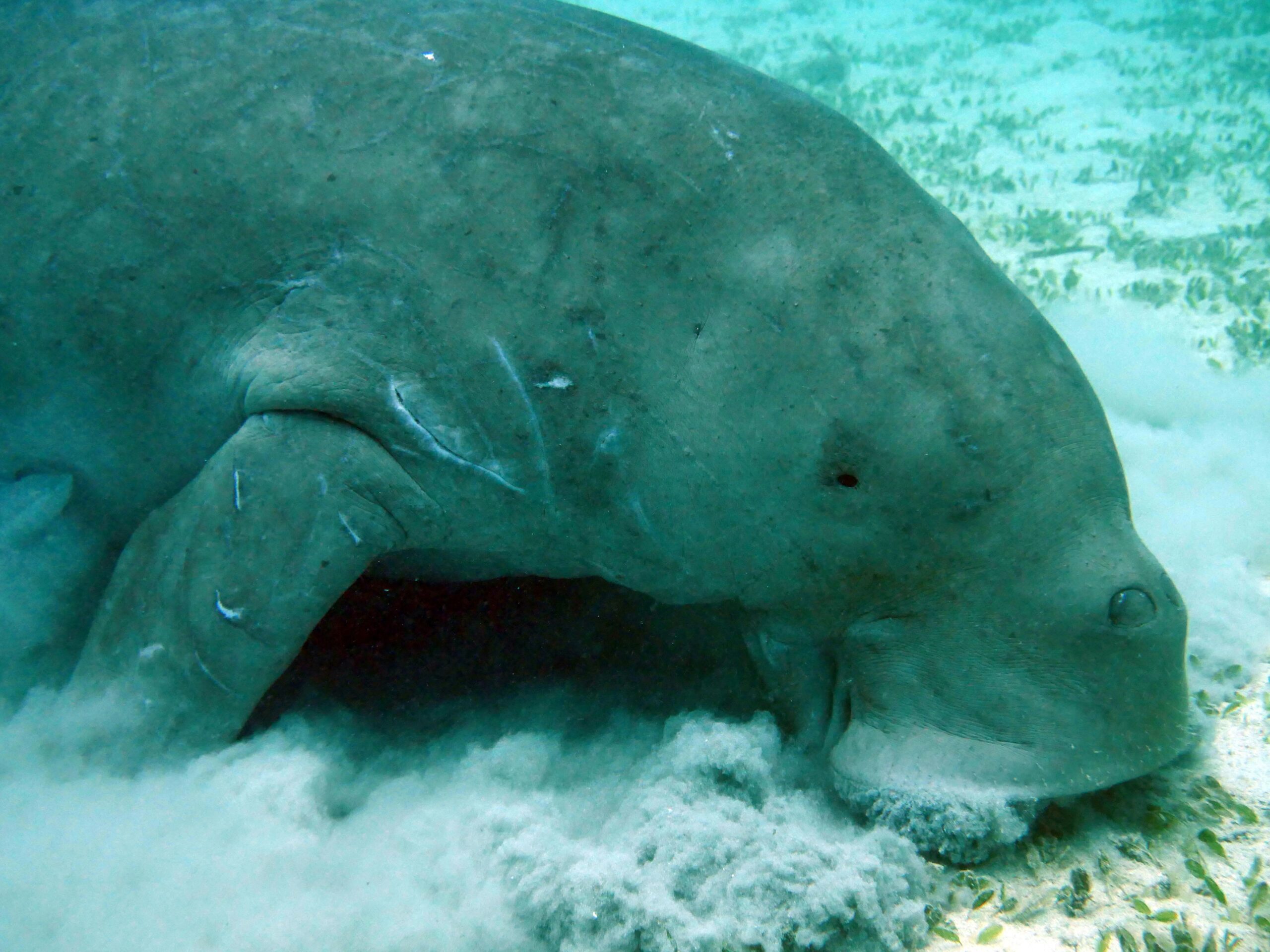

Photo by Ray Aucott

Thailand’s Andaman Coast dugong population may have fallen by more than half in recent years, as more dead or stranded animals wash ashore pointing to a larger biodiversity crisis in the world’s seas.

The Andaman Coast is home to one of the largest dugong populations in the world, with 273 of the plump marine mammals, sometimes called sea cows, estimated to be living there as of 2022.

Documentary investigation

Guardian journalist Gloria Dickie travelled to Phuket in late November, following in the footsteps of film-makers Mailee Osten-Tan and Nick Axelrod, who have been investigating Thailand’s dugong crisis over the past year for a new Guardian documentary.

The reason that dugongs are in Phuket to begin with is troubling, and points to the larger biodiversity crisis in our seas.

At a roti shack on the edge of Tang Khen Bay, Dickie met Theerasak Saksritawee, known as Pop, a local photographer who has been recording the plight of dugongs via captivating drone images. He hopes to share more about dugongs with his 26,000 followers on Instagram, building a social movement to champion their protection.

Pop said: “Many people, when they think of conservation, focus on sea turtles and dolphins. Some people can’t even tell where a dugong’s eyes are.”

Territorial behaviour

Just before meeting Pop, Dickie had been attacked by a large Chinese goose. The territorial animal had grown used to Pop’s presence along the shoreline day after day, and was protective of him.

The goose was reminiscent of Miracle – the lone dugong left in Tang Khen Bay as of late 2025. At one point, there were as many as 13 dugongs living in the bay, nibbling the stubbly seagrass that sprouts along the ocean floor. But Miracle – who earned his name for having twice been saved from beach strandings – had chased the others away, biting at their flippers to keep the seagrass to himself.

Migration from Trang

The fact that dugongs are present in Phuket worries environmental scientists. Normally, the bulk of the Andaman Coast population resides 62 miles (100km) away in the waters of Trang province, home to abundant seagrass meadows. A lot of that seagrass, however, has died in recent years. And in response, dugongs are travelling farther and farther in search of food.

Multiple environmental stressors

Scientists say they still aren’t entirely sure what has caused the massive seagrass die-off, but it’s likely a combination of shifting environmental factors: reduced light reaching the seagrass due to silt in the water; pollution; dredging; more dissolved nutrients in the system; extreme sea temperatures; and elevated daytime tidal exposure.

Thailand’s Andaman Sea actually experienced cooler temperatures than normal in 2023, and by the time it reached unseasonably high temperatures in mid-2024, the dugong strandings and deaths were already in full swing.

High seas treaty

One hope for tackling the many complex crises happening in our oceans is the UN’s high seas treaty, which entered into force at the weekend. This agreement aims to legally protect and sustainably manage marine life in the two-thirds of the ocean that lie beyond national jurisdiction. This will help to meet a global goal of protecting 30 per cent of the world’s oceans by 2030.

After leaving Tang Khen Bay, Dickie travelled to Phuket’s old town, where it was the beginning of the high season. She searched among the keyrings and shell jewellery for anything resembling a dugong – a sign that the animals were beginning to gain cultural cache in this tourist hotspot. In the end, she managed to turn up just one pin for sale featuring a cartoonish dugong – with clearly visible eyes.