Image description: A plastic bottle, polystyrene and driftwood on a sandy beach. Image by Catherine Sheila/ Pexels.

Not a single inch of the Mediterranean is clean

A new study has shone a light on one of the highest concentrations of deep-sea litter ever detected at the deepest point of the Mediterranean Sea.

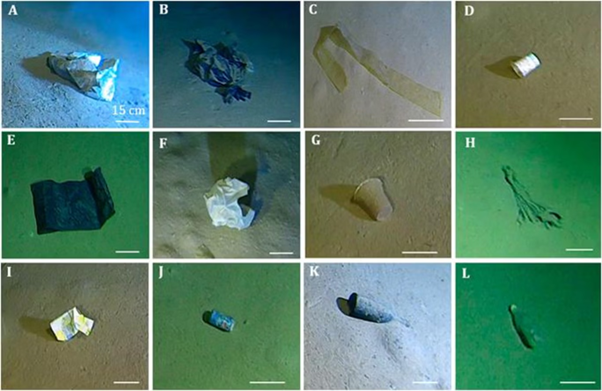

Scientists captured photos of litter at the bottom of the Calypso Deep, a trench 16,771ft (5,112m) below the surface of the Ionian Sea. A total of 167 objects – made of plastic, glass, metal and paper – have been identified at the bottom. Significantly, the study noted plastic accounted for nearly 90 per cent of the litter material.

Researchers from the University of Barcelona said the debris was likely carried to the Calypso Deep by ocean currents and direct dumping by boats. This includes plastic bags, a plastic sack, plastic food containers, plastic cups and lids, plastic rope, paper cartons, metal drinks cans and glass bottles. Due to the trench forming a “closed depression” with weak currents, it favours the accumulation of debris. Professor Miquel Canals, one of the study’s authors, said: “Unfortunately, as far as the Mediterranean is concerned, it would not be wrong to say that ‘not a single inch of it is clean”.

Image Description: A grid showcasing debris identified in Calypso Deep. Image by Caladan Oceanic.

Avalanches of microplastics

Another recent study has also provided the first direct evidence for the role of fast-moving underwater avalanches, known as turbidity currents, in transporting vast quantities of microplastics into the deep sea.

Of more than 10 million metric tons of plastic waste entering the oceans each year, visible waste accounts for less than 1% of the total. The missing 99%, primarily made up of fibers from textiles and clothing, is instead sinking into the deep ocean.

The findings, published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, show that these powerful flows could be capable of traveling at speeds of up to eight meters per second, carrying plastic waste from the continental shelf to depths of more than 3,200 meters.

Research on microplastic hotspots in the Tyrrhenian Sea by the University of Manchester, published in the journal Science, were among the first to demonstrate that turbidity currents play a major role in distributing microplastics across the seafloor. However, the latest study, conducted by the University of Manchester, the National Oceanography Center (UK), the University of Leeds (UK), and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, provides the first field evidence showing the process in a real-world setting. By combining in-situ monitoring and direct seabed sampling, the team were able to witness a turbidity current in action, moving a huge plume of sediment at over 2.5 meters per second at over 1.5 km water depth.