By Keith Hiscock, Associate Fellow, Marine Biological Association

Marine life in the seas around Britain is diverse: from the colourful anemones in rockpools to huge basking sharks. Our oceans are important socially and economically – they provide us with healthy food and other resources, they benefit our mental health and physical wellbeing, and offer endless recreational opportunities, from fishing to watersports. Global UN targets to protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030 involve establishing more marine protected areas.

The conservation of biodiversity depends on an understanding of how an environment works, what might threaten its habitats and species and how best to restore what has been damaged. As a marine scientist who has worked in this field for more than five decades, I worry that, although marine conservation around Britain has shown some success, many of the tools that are in use today are irrelevant, broken, blunt or missing.

Here are five ways to improve marine biodiversity conservation around Britain:

1. Reconsider connectivity

Marine conservation advisors often refer to connectivity distances – ensuring that species will be able to move between or recolonise locations, especially separate marine protected areas. On land, wildlife corridors are areas such as hedgerows that link habitats and species together. However, the sea is a fluid medium through which marine animals can travel. Species that migrate (including in their young stages as larvae) can swim or drift through the water. So isolated reef habitats, for example, don’t have to be physically joined as they might need to be on land. Connectivity considerations are, however, important where there are separate breeding, feeding or resting areas for a species, or where potential for recovery from damage or loss is being considered.

Rare, scarce and sensitive marine life in one of the Isles of Scilly’s Marine Conservation Zones which lists only spiny lobsters and moderate energy intertidal rock for protection. Keith Hiscock, CC BY-ND

Connectivity does not need to be prioritised as highly as it does on land – accepting this will save time and avoid inappropriate design of marine protected areas as a network. Letting go of the concept of networks could increase the designation of locations where threatened species and habitats occur.

2. Rethink viability

Viability, in this instance, refers to the ability of a marine species to live, grow and reproduce in a marine protected area. The size of a protected area will vary according to context so a set minimum size isn’t always transferable to all species or habitats. For example, anemones or corals attached to a small reef rely on the water column for nutrients and only need that area protected whereas fish that are moving around might need a larger foraging territory.

Poor use of the knowledge that we already have about how marine creatures survive and thrive has led to minimum size limits of marine protected areas being set – but sometimes smaller areas would actually be viable and worthwhile. For example, Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel is a successful no-take zone (an area where no fishing is permitted) but at only 4km in length, it doesn’t meet the 5km minimum size requirement to be classed as an English highly protected marine area with the strictest possible protection. So better use of scientific knowledge is needed to adapt conservation measures according to the needs of the specific species and habitats being protected.

3. Assess threats more accurately

Government advisers and licensing authorities need reference lists of species and habitats that are rare, scarce, valued or sensitive to pressures brought about by human activities.

One human activity may pose a serious threat to one marine species but not another. Assessing the degree of threat – the amount of risk posed to marine wildlife by something like dredging or trawling – needs to be based on the latest scientific evidence and the sort of systematic approach developed by the Marine Life Information Network database.

Most (60%) habitats in the north-east Atlantic fail to be considered for protection from human activities because of a lack of data on population decline, geographical range or rarity of associated species.

The seagrass bed at Skomer failed to qualify as a designated feature because it was smaller than the specified minimum Blaise Bullimore, CC BY-ND

Rarity is a useful consideration but the catalogue of nationally rare and scarce species was last published in 1996. Since then, there have been range extensions of north-east Atlantic species to Britain (such as the ringneck blenny) and species new to science have been described.

Differences in the life histories of species also need to be taken into account when considering degree of threat and more species and habitats assessed for sensitivity or irreplaceability. Animals with contrasting life cycles need different responses. Some larvae are short-lived and fast growing, others are long-lived and slow growing, while some disperse widely. These variations need to be considered.

Issues of data deficiency were greatly overcome via the Nationally Important Marine Features initiative and a list first defined in 2003 – this initiative needs to be resurrected and updated regularly.

4. Reduce the need for licensing

Several scientists I have spoken to agree that excessive bureaucracy, by the Marine Management Organisation in particular, often involves complicated and time-consuming licensing procedures that may stifle scientific studies that inform conservation. My own application to observe and photograph seahorses took 102 days to process. Marine conservation projects need more guidance and less licensing.

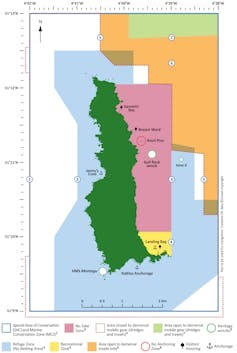

The Lundy Marine Protected Area has a zoning scheme that includes (in pink) a successful Highly Protected Marine Area less than 4km in length – that’s smaller than the now minimum size for these Highly Protected Marine Areas in England. Keith Hiscock, CC BY-ND

5. Improve management

Marine Protected Areas are frequently seen as just lines on a map without management regimes. Each one needs a clear management plan that identifies all of the species and habitats that need protection in that location. Some approaches have recently been pursued and are promising: the whole site approach considers the integrity of a site as a whole, not just designated features, while Highly Protected Marine Areas prohibit activities that are extractive (mainly fishing) and destructive (such as dredging), allowing only non-damaging levels of other activities such as recreational watersports.

It’s time to throw out tools that do not work, sharpen the blunt ones, reinstate abandoned but effective ones and create new tools. Lists, databases and websites need to be constantly updated with information that’s easily understood – even by non-scientists. Ultimately, more consistent monitoring of the state of our seas underpins marine conservation success.

This piece is by Keith Hiscock, Associate Fellow, Marine Biological Association, and first published in The Conversation.