Norway has become the first country in the world to move forward with commercial-scale deep-sea mining.

The bill, passed in the Norwegian Parliament, will accelerate the exploration for precious metals which are in high demand for green technologies. Scientists have warned it could be devastating for marine life.

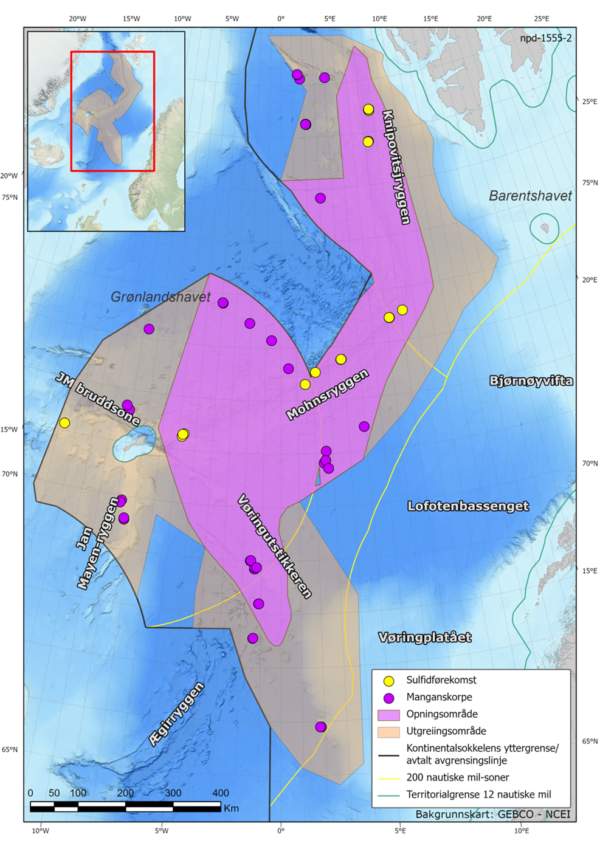

Norway’s parliament voted 80–20 in favour of allowing exploratory mining on the continental shelf in the Norwegian Sea. The aim is to map the sea bed in the country’s jurisdiction and investigate whether sulfides and manganese crusts — currently mined on land — could be extracted profitably from the sea floor.

What and where would be mined?

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate estimates that the country’s seabed contains large stores of cobalt, copper and rare earth metals at depths between 1,500 and 6,000 meters (4,900 to 19,700 feet). The copper reserves alone are projected to be 38 million metric tons, nearly twice annual global production of the metal.

Area open for deep sea mining shown in purple. Source: Norwegian Offshore Directorate

Norway is targeting metals that have accumulated over millions of years in the crusts of seamounts, which have been shown to be hotspots for marine life. Norway said it wouldn’t mine active hydrothermal vents but would focus on so-called massive sulfide deposits near inactive vents, Mining.com reported.

Extracting those metals would mean deploying robots to strip the upper layers of seamounts and sulfide deposits. Scientists say that would be more ecologically destructive than the type of mining currently under consideration by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). The ISA is currently focused on mining conducted by companies targeting polymetallic nodules. These potato-sized rocks contain cobalt and nickel and cover the Pacific Ocean seabed by the billions, but aren’t found in Norwegian waters.

Scientific advice

Norwegian scientists say they are disappointed but not surprised by the move. They say that the government ignored their scientific advice and that of the nation’s environment agency in Trondheim. In response to a public consultation on the government’s mining plans, scientists said that too little is known about the biodiversity and ecosystem functions of the proposed sites to enable mining to go ahead safely.

“How can we make meaningful judgements of acceptable harm or risk when we know absolutely nothing about it?” says Peter Haugan, director of policy at the Institute of Marine Research in Bergen.

Helena Hauss, a marine ecologist at NORCE, an independent research institute with headquarters in Bergen, says that the proposed mining sites are inhabited by communities not found elsewhere, and will be irreversibly damaged. “This is difficult to align with the claim of the Norwegian government that this will be done in a sustainable and responsible way,” she says.

More than 800 scientists have signed an open letter in support of a pause on deep sea mining, warning of potentially “irreversible” damage to the ecosystem.

According to a study by the Environmental Justice Foundation published on the day of the vote, deep-sea mining is not needed for the clean energy transition.

International negotiations

The EU and the UK have called for a temporary ban on the practice of deep-sea mining because of concerns about environmental damage.

While Norway’s proposal concerns its national waters, negotiations continue on whether licences could be issued for international seas.

The ISA will meet this year to try to finalise rules in international waters, with a final vote expected in 2025.