As the world meets to agree its latest plans to combat climate change at the UN Climate Change COP27, and others simultaneously meet in the often overlooked COP14 Ramsar discussions, WWT’s new Wetlands For Carbon Storage Route Map calls for the creation of at least 22,000 hectares of coastal saltmarsh by 2050 to help the UK government reach its net zero targets.

Reaching 22,000 hectares (an area twice the size of Bristol) could store 1.5 megatonnes of carbon dioxide every year – equivalent to taking 770,000 cars off the road for one year.

As a priority, it is calling for the government to help release funding and support by incorporating saltmarsh creation into its key climate policies – specifically it’s Nationally Determined Contributions and the UK Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

The report also calls for the Saltmarsh Carbon Code currently being developed by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH) to be adopted by UK government and devolved administration by 2025. This code could unlock private investment to create, restore and effectively manage more saltmarsh – similar to the positive effect the existing woodland and peatlands code have had on investment in these habitats.

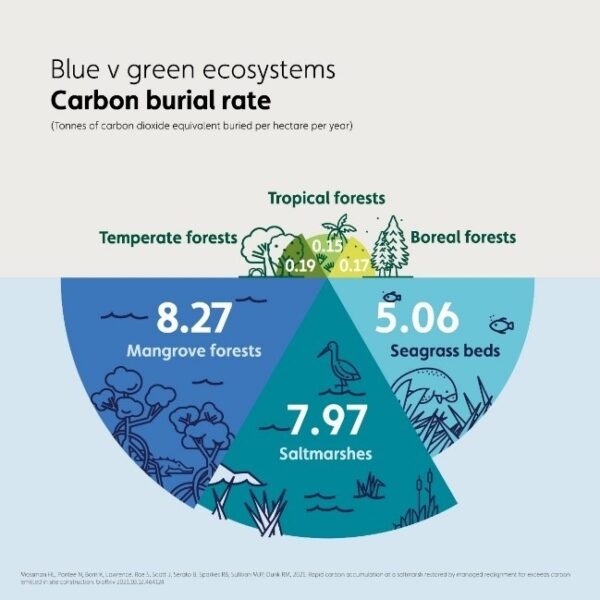

Dr James Robinson, WWT Director of Conservation, said “Evidence is mounting that coastal wetlands such as saltmarsh could be more effective than trees in the fight against accelerating climate change. Statistics which tell us that peatlands and coastal wetlands put together store more carbon than all of the world’s forests combined, and that carbon is typically captured 40 times faster by saltmarsh than temperate forests[iii] are hard to ignore. The government have embraced tree planting in climate policy which we welcome, but we need the same approach for saltmarsh. As an island, we could, and should, be world-leading in harnessing the benefits of this vital habitat at scale.”

WWT say that ‘saltmarsh is so efficient at locking away carbon because when saltmarsh plants die, rather than decomposing and releasing their carbon back into the atmosphere as plants do when they die above ground, they become buried in low-oxygen mud locking away the carbon, in some cases indefinitely. In addition, as sea levels rise more sediment layers get buried and more carbon gets locked beneath the mud.

Saltmarshes bring a range of other benefits beyond storing carbon. They help reduce flood risk, improve water quality through filtering pollutants, are globally important for migrating water birds, provide a home to 40 species that only exist in saltmarsh and offer new economic opportunities to local communities including farming. They are conservatively estimated to be worth around £3 million annually to the commercial landings of European seabass, common sole and European plaice.’

The WWT report, Wetlands for Carbon Storage – Creating and managing saltmarshes to store blue carbon in the UK: A Route Map, can be read here.