How old is your water? It may seem like a peculiar question at first, but there are real implications to how long a drop of water has spent underground. Research suggests that the water cycle is speeding up in some places as a result of human enterprise.

Scientists at UC Santa Barbara discovered that relatively young groundwater tends to reach deeper depths in heavily pumped aquifer systems, potentially bringing surface-borne pollutants with it. The study, led by recent postdoctoral fellow Melissa Thaw, appears in Nature Communications.

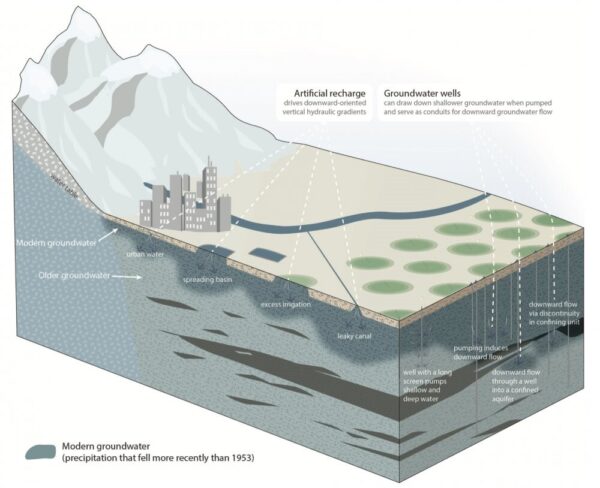

“We usually think deep groundwater is safe from the contaminants found closer to the Earth’s surface,” said Thaw. “However, intensive groundwater pumping is pulling recently replenished groundwater to deeper depths, potentially pulling contaminants down, too.”

Groundwater takes time to move about the subterranean world, flowing between soil particles and through crevices in the rock. Today’s raindrops might not be tomorrow’s well water; in fact, they might not even be next decade’s well water. “Half or more of all the groundwater stored on the planet is rain and snow that fell more than 12,000 years ago,” said Scott Jasechko, an associate professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. Intuitively, the deeper you look, the older the water generally is.

Thaw and fellow postdoc Merhawi GebreEgziabher GebreMichael worked with senior author Jasechko and Jobel Villafañe-Pagán, an undergraduate student at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, who joined the team via the Geosciences Education & Mentorship Support program. Together, the authors sought to determine how pumping affects the movement of groundwater. To this end, they leveraged a dataset of concentrations of a rare form of hydrogen, known as tritium, in 15,000 groundwater wells across the contiguous United States.

They found there is a correlation between groundwater pumping and the depth that young groundwater reaches, even after considering an area’s geology.

The situation is a bit like drinking a slushy through a straw. You get the bottom stuff (old water) first and this draws in the top stuff (new water) to replace it. Except in this example, the slushy is periodically refilled from the top. Scientists call this phenomenon “pumping-induced downwelling.”

The authors believe their results reflect trends in other regions as well. “Our analysis of dozens of aquifer systems across the U.S. captures a wide array of variability in natural conditions and human activities,” Jasechko said. Still, he intends to extend some of this research globally. He plans to examine tritium profiles in other major aquifer systems around the world, especially those where groundwater withdrawal rates are high.

This is an extract from PhysOrg and the full story can be read here.

The full research article ‘Modern groundwater reaches deeper depths in heavily pumped aquifer systems’ in Nature Communications can be read here.

No Comment